This was supposed to be Friday's post, but real life decided to intervene before I could complete it. These days, my schedule is not completely my own.When talking to non-hobbyists, I find it’s usually easiest to describe live showing as a shrunken down version of the real thing. However, this comparison only works to a point. Not all breed associations offer “halter” classes at their shows and those that do each play by their unique set of rules.

And then there’s fashion. A written breed standard is rarely amended, let alone substantially altered, but the current aesthetic in all halter shown breeds appears to be in constant flux. In some breeds, halter bloodlines have become so specialized they’ve virtually become a breed within a breed. For illustrative purposes, I’m going to use the Quarter Horse as the most dramatic example of this split, but the same issues apply to a number of breeds including other stock breeds, Arabians, and Morgans. Cutting, reining, roping, pleasure, hunter, racing, and halter have all split out to varying degrees within the AQHA, but no type is excluded from a model horse halter class.

When I judge a model QH class, I know I have options on how I can approach it. The first option is to judge it as a real world halter class and choose horses that best represent this physical type:

This is CK Kid, and as much as it pains me to say so, he was an AQHA World Champion in halter.

If he were a model horse, I’d say his legs are too small and his back is too short in proportion to his body. Top to bottom, he is completely upright with no body angles to absorb any shock from movement. This much muscle (1500 pounds on a 16H horse) on top of double-ott feet is a recipe for disaster. I’d tell you this horse wouldn’t be able to run correctly with his conformation and is susceptible to a premature death. Considering his sire, dam sire, and grand-sire died at 9, 16, and 12 respectively, it’s a safe bet this 9-year-old stud doesn’t have many years left.

Referring back the judging elements

I previously outlined, this horse is typey but not well conformed. His proportions border on unrealistic, which is a concept that makes my head hurt.

As a judge, my second (and preferred) option is a holistic approach. I know QHs include a wide range of body types, each bred to serve a specific function. At live shows, we show all types, ideally with no bias. I try to judge each against their own type, i.e. reiners should look like this, pleasure horses should look like that, and so on. Type-y-ness may be a tiebreaker only in that I prefer a model that is easily recognizable as it's assigned breed, but it’s not my first concern.

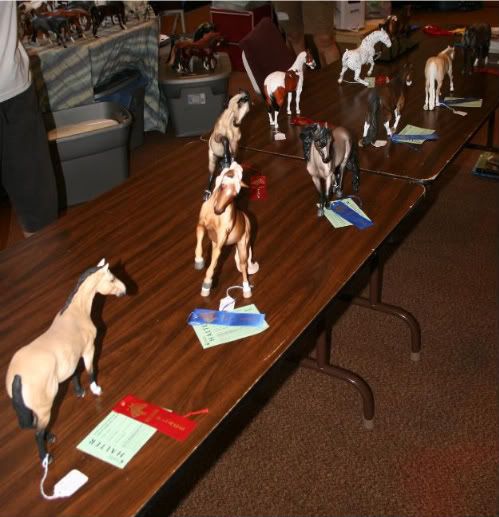

In contrast to the above, let’s look at a National Champion model halter horse:

This is a model I would love to have for my own show string. Her shading and collectibility both add to the “wow” factor, but for the purposes of this post, I’m only going to cover her conformation.

Overall, her build is lighter than the behemoth above, but there is no mistaking her for anything other than a stock horse. Her legs and hooves are substantially larger and better built to withstand the physical stresses of athletics. If she were a live horse, I’d guess she's bred for roping or gaming but with the potential for more. She’s balanced and well muscled, with straight legs and good body angles.**

In addition to various modern types, as a model horse judge I frequently encounter horses shown as historical breeds and types. In these cases, make or break often depends on quality documentation (future post.) This kind of breed assignment is usually chosen because colors are often eliminated from a breed and physical types evolve. However, the basics of functional conformation stay the same, as the below horse attests:

Peter McCue, AQHA Hall of Fame inductee.

Peter McCue, AQHA Hall of Fame inductee.Not perfect, but the basic angles are correct and a glance at his record testifies that his conformation was more than functional. He was a successful racehorse, but an even more successful stud and founding stallion of the AQHA. He’s built like a horse that could have walked out of a QH breeder’s barn today, but he was born in 1895.

A modern Quarter Horse with similar conformation, born over a century later.

A modern Quarter Horse with similar conformation, born over a century later.When the AQHA was formed 45 years later, his genes were what they sought to perpetuate. This is his descendant, Wimpy P-1, a grand champion stallion and the first horse registered with the AQHA:

Of the five photos I’ve included in the entry, which of these horse is not like the others? Hint: It’s not the model. (It’s CK Kid.)

Tune in for next week's post, when I continue to rattle on about Quarter Horses (just the model kind.)

**Speaking of body angles, is conformation a topic anyone would like to hear about from me? Please let me know in the comments.