Tuesday, October 13, 2009

Get Your Flu Shot

I put it off for a few days, then got on a plane, and now I'm seriously regretting it. I'll be out of commission for a few days.

Monday, October 12, 2009

Basic Dressage: Pt. 1

Today's guest blogger is Cassie Black, a hobbyist who has shown dressage extensively and trained her own horse through Prix St George:

Basic Dressage for the Model Shower

Dressage is the training of the horse. It is not breed specific and is open to all horses and mules. This training is judged based on a series of movements within a test. Horses are shown at different levels based on their training, Intro level through 4th level are govererned by the USEF and the International levels, Prix St George, Intermediate I, Intermediate II and Grand Prix are governed by the FEI.

Arena

The Dressage arena is a 60 X 20 meter rectangle with a low fence. The Letters around the rail are A-K-V-E-S-H-C-M-R-B-P-F, G-I-X-L-D are not letters on the rail, they are considered invisible letters, and if they are seen they are small under the main rail letters.

Tack

Horses may be shown in any English saddle. The saddle must have stirrups and can be shown with or without a saddle pad (square pads are generally seen.) A Dressage saddle (long flaps) is required for FEI levels.

Bridles for training, first, and second levels must be a plain snaffle with a noseband. A simple double bridle is required for the FEI levels, and is optional for third and fourth level.

Numbers are generally small ovals worn on the side of the browband, just be sure that they are not pinching an ear or covering eyes.

Levels

(revised from USEF rulebook 2009)

These levels are the most important part of showing your model horse in Dressage. The horse should fit into one of these descriptions to do well. Dressage horses should be on the bit, quiet, forward and round over their topline. The models listed after each level are just examples, they can be interchangeable up or down a level and are by no means an exhaustive list.

INTRO LEVEL: A Walk-Trot test for the beginning horse or rider

(Breyer Marigold “Morgan”)

TRAINING LEVEL: To confirm that the horse’s muscles are supple and loose, and that it

moves freely forward in clear and steady rhythm, accepting contact with the bit.

(Peter Stone Pebbles WB, Breyer John Henry)

FIRST LEVEL: To confirm that the horse, in addition to the requirements of Training Level, has

developed thrust (pushing power) and achieved a degree of balance and throughness.

(Top Hat and Tails-Resin)

SECOND LEVEL: Through additional training, the horse accepts more weight on the hindquarters (collection), shows the thrust required at medium paces and is reliably on the bit.

(Utopia-resin, SM Cantering WB)

THIRD LEVEL: The Horse now demonstrates in each movement: rhythm, suppleness, acceptance of the bit, throughness, impulsion, straightness, and collection. There must be a clear distinction between the paces.

(Smittyn-resin, Meridian-resin)

FOURTH LEVEL: The horse has acquired a high degree of suppleness, impulsion, throughness, balance and lightness while always remaining reliably on the bit, and that its movements are straight, energetic and cadenced with the transitions precise and smooth.

(Dinky Duke-resin, Ricardo-resin)

Basic Dressage for the Model Shower

Dressage is the training of the horse. It is not breed specific and is open to all horses and mules. This training is judged based on a series of movements within a test. Horses are shown at different levels based on their training, Intro level through 4th level are govererned by the USEF and the International levels, Prix St George, Intermediate I, Intermediate II and Grand Prix are governed by the FEI.

Arena

The Dressage arena is a 60 X 20 meter rectangle with a low fence. The Letters around the rail are A-K-V-E-S-H-C-M-R-B-P-F, G-I-X-L-D are not letters on the rail, they are considered invisible letters, and if they are seen they are small under the main rail letters.

Tack

Horses may be shown in any English saddle. The saddle must have stirrups and can be shown with or without a saddle pad (square pads are generally seen.) A Dressage saddle (long flaps) is required for FEI levels.

Bridles for training, first, and second levels must be a plain snaffle with a noseband. A simple double bridle is required for the FEI levels, and is optional for third and fourth level.

Numbers are generally small ovals worn on the side of the browband, just be sure that they are not pinching an ear or covering eyes.

Levels

(revised from USEF rulebook 2009)

These levels are the most important part of showing your model horse in Dressage. The horse should fit into one of these descriptions to do well. Dressage horses should be on the bit, quiet, forward and round over their topline. The models listed after each level are just examples, they can be interchangeable up or down a level and are by no means an exhaustive list.

INTRO LEVEL: A Walk-Trot test for the beginning horse or rider

(Breyer Marigold “Morgan”)

TRAINING LEVEL: To confirm that the horse’s muscles are supple and loose, and that it

moves freely forward in clear and steady rhythm, accepting contact with the bit.

(Peter Stone Pebbles WB, Breyer John Henry)

FIRST LEVEL: To confirm that the horse, in addition to the requirements of Training Level, has

developed thrust (pushing power) and achieved a degree of balance and throughness.

(Top Hat and Tails-Resin)

SECOND LEVEL: Through additional training, the horse accepts more weight on the hindquarters (collection), shows the thrust required at medium paces and is reliably on the bit.

(Utopia-resin, SM Cantering WB)

THIRD LEVEL: The Horse now demonstrates in each movement: rhythm, suppleness, acceptance of the bit, throughness, impulsion, straightness, and collection. There must be a clear distinction between the paces.

(Smittyn-resin, Meridian-resin)

FOURTH LEVEL: The horse has acquired a high degree of suppleness, impulsion, throughness, balance and lightness while always remaining reliably on the bit, and that its movements are straight, energetic and cadenced with the transitions precise and smooth.

(Dinky Duke-resin, Ricardo-resin)

Thursday, October 8, 2009

Collecting China Horses

I'm wrapping up China Week with Melissa Gaulding's article on collecting china. If I can get internet access tomorrow, there will be a bonus post on Friday (on performance!) to make up for my lack of post on Monday.

Ceramic is the overall term for things made from clay that are fired in a kiln. In the model horse hobby community, we call them chinas, or clinkies, and we refer to ourselves as chinaheads!

How are ceramic horses made?

How are ceramic horses made?

China horses are made from different clays; the clays are fired at different temperatures to harden and stabilize them. There are two types of clay you will see most often: earthenware and bone china.

Earthenware is more common, easier to make in a home studio, but more fragile. Earthenware does not radically change during the firing process; it remains porous and grainy. It is the clay used by Hagen Renaker and Pour Horse Pottery.

Bone china is a bit more resistant to breaks, harder, and more expensive to produce. Like its “cousins,” porcelain and stoneware, bone china will vitrify, or fuse to a glass-like consistency, when fired¬¬—this makes these materials hardier than earthenware, which does not vitrify. Bone china has calcium carbonate—often from actual bones—in it. Horsing Around and Animal Artistry mostly use bone china.

China horses come out of their molds in moist clay form, called greenware. Greenware must be completely dry before it can be fired in a kiln. The resulting piece, from this initial firing, is called bisque. Bisqueware is the color of the original clay. Bisques can be finished in many ways—they can even be cold-painted.

(If a horse in its greenware state is resculpted or changed from its molded form, it is called a claybodied custom, and is automatically a glazed custom for show purposes, regardless of coloring.)

China horses are usually under-painted (also called "under-glazed") with fragile liquid clays (called slip) that have chemicals in them that change color when fired in a kiln—underglazed pieces then have a clear glaze applied over them and are refired (this is what Joan Berkwitz of Pour Horse does). Glaze is the powdered glass suspended in liquid that melts in the kiln to form a clear or matte protective coating that seals the color onto the china horse. Chinas can also be glazed first and then china painted, or over-painted with colors that are fired on and sink into the glaze (Karen Gerhardt does this beautifully). Whether underglazed or china painted, most horses require several firings to “bake” the colors and achieve the desired outcome.

Not all chinas are glossy. There are satin and matte glazes in use now, so the horse does not have to be shiny. Vintage Hagen Renakers have a matte glaze that cannot be used anymore for safety reasons, due to lead content; Britain does not have the same mandates as the US and may be able to use chemicals we can't, so matte glazes are commonly seen on British-produced horses. Many contemporary artists are having luck with "safe" matte glazes, but these can be tricky to work with—if applied too thickly, the matte glaze can frost and ruin the horse.

Bone china takes finishes differently than earthenware, and many bone china pieces are not finished with underglazes, but rather china painted, which will produce a different look to the finished piece. Bone china is not porous, so coloring it is different than earthenware—also, bone china is a cooler white, whereas earthenware is a warmer white—these differences effect the end results of underglazing the piece (for example, the same gray on a bone china will look more blue than on earthenware). Bone china generally involves more steps to completion than earthenware, although this also depends on the complexity of the finish.

What is the difference between OF chinas and glazed custom chinas?

Earthenware is more common, easier to make in a home studio, but more fragile. Earthenware does not radically change during the firing process; it remains porous and grainy. It is the clay used by Hagen Renaker and Pour Horse Pottery.

Bone china is a bit more resistant to breaks, harder, and more expensive to produce. Like its “cousins,” porcelain and stoneware, bone china will vitrify, or fuse to a glass-like consistency, when fired¬¬—this makes these materials hardier than earthenware, which does not vitrify. Bone china has calcium carbonate—often from actual bones—in it. Horsing Around and Animal Artistry mostly use bone china.

China horses come out of their molds in moist clay form, called greenware. Greenware must be completely dry before it can be fired in a kiln. The resulting piece, from this initial firing, is called bisque. Bisqueware is the color of the original clay. Bisques can be finished in many ways—they can even be cold-painted.

(If a horse in its greenware state is resculpted or changed from its molded form, it is called a claybodied custom, and is automatically a glazed custom for show purposes, regardless of coloring.)

China horses are usually under-painted (also called "under-glazed") with fragile liquid clays (called slip) that have chemicals in them that change color when fired in a kiln—underglazed pieces then have a clear glaze applied over them and are refired (this is what Joan Berkwitz of Pour Horse does). Glaze is the powdered glass suspended in liquid that melts in the kiln to form a clear or matte protective coating that seals the color onto the china horse. Chinas can also be glazed first and then china painted, or over-painted with colors that are fired on and sink into the glaze (Karen Gerhardt does this beautifully). Whether underglazed or china painted, most horses require several firings to “bake” the colors and achieve the desired outcome.

Not all chinas are glossy. There are satin and matte glazes in use now, so the horse does not have to be shiny. Vintage Hagen Renakers have a matte glaze that cannot be used anymore for safety reasons, due to lead content; Britain does not have the same mandates as the US and may be able to use chemicals we can't, so matte glazes are commonly seen on British-produced horses. Many contemporary artists are having luck with "safe" matte glazes, but these can be tricky to work with—if applied too thickly, the matte glaze can frost and ruin the horse.

Bone china takes finishes differently than earthenware, and many bone china pieces are not finished with underglazes, but rather china painted, which will produce a different look to the finished piece. Bone china is not porous, so coloring it is different than earthenware—also, bone china is a cooler white, whereas earthenware is a warmer white—these differences effect the end results of underglazing the piece (for example, the same gray on a bone china will look more blue than on earthenware). Bone china generally involves more steps to completion than earthenware, although this also depends on the complexity of the finish.

What is the difference between OF chinas and glazed custom chinas?

The short version is that it is just like plastics: there are OFs produced in a factory (Hagen Renakers and Breyer porcelains) and there are artist chinas produced by artists, often in their own studios (like Lynn Fraley and Kristina Lucas-Francis). Also like plastics, there are vintage pieces (although chinas can be much older than injection-molded plastic horses) and contemporary pieces.

OFs, or original finishes, are produced in large numbers; these can also be called production runs. One of a kind or glazed customs are generally produced by an individual artist, like Lesli Kathman or Adalee Velasquez.

Who makes china horses?

OFs, or original finishes, are produced in large numbers; these can also be called production runs. One of a kind or glazed customs are generally produced by an individual artist, like Lesli Kathman or Adalee Velasquez.

Who makes china horses?

China horses have been made for centuries all over the world! But our community tends to collect and show the most realistic-looking ceramic horses.

There are European-produced chinas (Royal Copenhagen for example) and US produced pieces like Hagen-Renaker.

Maureen Love (also known as Maureen Love Calvert) was the main Hagen Renaker sculptress for horses, and she sculpted all the beloved vintage pieces: Amir, Zara, Zilla, Heather, Harry, Adelaide, Kelso, Terrang, etc.

Other sculptors of note for vintage European pieces: Theodore Karner and Doris Lindner and Pamela DeBoulay.

Donna Chaney in the UK produces chinas as well as her resins, as does Horsing Around—Mark and Vanessa Crawley get rights to sculptures by many of the top resin artists (Eberl, Bogucki, Rose) and make them into chinas. Both these outfits mostly make bone chinas, although Donna Chaney has recently introduced a line of earthenware horses.

Some of the artists in the US that are making chinas: Joan Berkwitz of Pour Horse (earthenware) and MarcherWare (bone china); Lesli Kathman, Paige Easley Patty, Adalee Velasquez, Lynn Fraley, Karen Gerhardt, Marge Para, Kristina Francis, Karen Grimm of Black Horse Ranch, Lynn Raftis, Karen Dietrich, Jenn Danza, D'arry Frank, Sarah Minkiewicz-Breunig---this list goes on and on.

There is a world of fascinating pieces in the Made In Japan—literally—chinas, many of them knock-offs of Hagens. And there are way more than I've described---the Model Horse Gallery talks a bit about some of the china factories, too.

Why should I buy such a fragile horse?

There are European-produced chinas (Royal Copenhagen for example) and US produced pieces like Hagen-Renaker.

Maureen Love (also known as Maureen Love Calvert) was the main Hagen Renaker sculptress for horses, and she sculpted all the beloved vintage pieces: Amir, Zara, Zilla, Heather, Harry, Adelaide, Kelso, Terrang, etc.

Other sculptors of note for vintage European pieces: Theodore Karner and Doris Lindner and Pamela DeBoulay.

Donna Chaney in the UK produces chinas as well as her resins, as does Horsing Around—Mark and Vanessa Crawley get rights to sculptures by many of the top resin artists (Eberl, Bogucki, Rose) and make them into chinas. Both these outfits mostly make bone chinas, although Donna Chaney has recently introduced a line of earthenware horses.

Some of the artists in the US that are making chinas: Joan Berkwitz of Pour Horse (earthenware) and MarcherWare (bone china); Lesli Kathman, Paige Easley Patty, Adalee Velasquez, Lynn Fraley, Karen Gerhardt, Marge Para, Kristina Francis, Karen Grimm of Black Horse Ranch, Lynn Raftis, Karen Dietrich, Jenn Danza, D'arry Frank, Sarah Minkiewicz-Breunig---this list goes on and on.

There is a world of fascinating pieces in the Made In Japan—literally—chinas, many of them knock-offs of Hagens. And there are way more than I've described---the Model Horse Gallery talks a bit about some of the china factories, too.

Why should I buy such a fragile horse?

Actually, china horses are not as fragile as many people think! As I like to say, “If you aren’t in the habit of breaking your glassware at home, you aren’t very likely to break your ceramic horses!” We learn to handle them carefully and repair them on the rare occasion when they do break.

Making ceramic figurines is a recognized art form that is thousands of years old. Both ancient and contemporary ceramic horses are beautiful, and bring feelings of enjoyment and wonder to the collector. With care, chinas will last for centuries. And they are more eco-friendly than plastic horses! Because coloring ceramic horses involves chemistry and heat, there is a magic to making them, never quite knowing exactly what the results will be. And because there are more limitations to the entire ceramic process, creating a perfect one is a complicated venture that can test the mettle of even the most talented artist.

Finally, ceramic horses tend to retain their value, and some (like vintage Hagen-Renakers) have exponentially increased in value over time.

Making ceramic figurines is a recognized art form that is thousands of years old. Both ancient and contemporary ceramic horses are beautiful, and bring feelings of enjoyment and wonder to the collector. With care, chinas will last for centuries. And they are more eco-friendly than plastic horses! Because coloring ceramic horses involves chemistry and heat, there is a magic to making them, never quite knowing exactly what the results will be. And because there are more limitations to the entire ceramic process, creating a perfect one is a complicated venture that can test the mettle of even the most talented artist.

Finally, ceramic horses tend to retain their value, and some (like vintage Hagen-Renakers) have exponentially increased in value over time.

Why are china horses so expensive?

Generally, collecting chinas is expensive—like collecting resins.

Chinas—especially one-of-a-kind or OOAK—can be moderately expensive or gaspingly expensive; if you are used to original finish plastic prices, and paying $50 or $100 for a horse makes you wince, then chinas will make you shake your head and go "Huh?!" Mostly the expense involved in purchasing chinas reflects the amount of work going into them and their relative rarity. Bone china is much more complicated to fire, so it tends to be more expensive to purchase.

Still, some very nice pieces can be found for a few hundred dollars. Watching AuctionBarn or MH$P can still yield bargains. There are also Breyer china horses and the Lakeshore OF chinas that are reasonably priced.

How should I display my ceramic horses?

Chinas—especially one-of-a-kind or OOAK—can be moderately expensive or gaspingly expensive; if you are used to original finish plastic prices, and paying $50 or $100 for a horse makes you wince, then chinas will make you shake your head and go "Huh?!" Mostly the expense involved in purchasing chinas reflects the amount of work going into them and their relative rarity. Bone china is much more complicated to fire, so it tends to be more expensive to purchase.

Still, some very nice pieces can be found for a few hundred dollars. Watching AuctionBarn or MH$P can still yield bargains. There are also Breyer china horses and the Lakeshore OF chinas that are reasonably priced.

How should I display my ceramic horses?

China horses are too lovely to keep packed away. Invest in a curio cabinet to display and keep your chinas safe. Unless a horse is quite tippy, it isn’t usually necessary to sticky wax them to a shelf, and this can result in snapping off a leg if not removed carefully! It can be hard to find someone to repair them, but fortunately it is relatively easy to learn to repair them yourself.

Can I show my ceramic horses?

Can I show my ceramic horses?

Yes! Many live model shows and most photo shows now have a division for china horses.

One example: Breyer SM chinas are factory-produced by the hundreds, so if you were to show them, they would go in the OF china classes. Much like showing OF plastics, you want the horse to be in top condition, and since they are shiny, they also need to be very clean---no big fingerprints or wisps of dust, please! A OOAK piece would show in glazed customs, if such classes are available.

Do ceramic horses hold their value?

One example: Breyer SM chinas are factory-produced by the hundreds, so if you were to show them, they would go in the OF china classes. Much like showing OF plastics, you want the horse to be in top condition, and since they are shiny, they also need to be very clean---no big fingerprints or wisps of dust, please! A OOAK piece would show in glazed customs, if such classes are available.

Do ceramic horses hold their value?

In our community, the piece's value is all about the collector and what she/he is willing to pay. There is no rule as to what holds its value, and has much more to do with rarity, condition, and desirability than it does with materials. For people who show, fads can also affect whether or not a piece holds its value. I don't think any ceramic is "better" than another---it is all personal preference.

Where can I learn more about ceramic horses?

Where can I learn more about ceramic horses?

There are more web sites devoted to china horses online than can be listed here, but a great place to start is Yahoo!groups Breakables, where many chinaheads hang out.

(The information written here is intended as an introduction; like most aspects of our hobby community, learning about ceramic horses is an on-going process—most chinaheads love to gab about china horses, so if you want to know more, ask them!)

(The information written here is intended as an introduction; like most aspects of our hobby community, learning about ceramic horses is an on-going process—most chinaheads love to gab about china horses, so if you want to know more, ask them!)

Wednesday, October 7, 2009

Judging Chinas: Workmanship

Once again, a huge thank you to guest blogger Melissa Gaulding!

Things to consider when judging glazed custom chinas in workmanship:

There are many, many wonderful achievements being made by our top finish artists in glazed custom chinas—perhaps too many to go into here, but a high degree of knowledge and control are needed for the artist to produce realism in this medium; these things should be rewarded in workmanship classes. Things listed below denote excellence in glazed custom workmanship (as with items listed above, sloppiness should be judged as it would in any medium).

• Because ceramic molds are plaster of paris, therefore completely rigid, complex poses are very difficult to achieve; some sculptures are cast in pieces and require extensive assembly by hand after casting, making each piece almost an original sculpture. The more complex the mold, the higher degree of difficulty in making a finished horse.

• Because ceramic materials (earthenware, bone china) require both great delicacy of handling plus a lot of handling to complete, thin legs, tiny ears, body/coat texture, and similar refined details are harder to make in ceramic casting.

• Because ceramic underglazes are not remotely the color when applied that they will be when fired, getting consistent results with color, shading, and coat details such as dappling isn’t easy (in glazed customs, orangey or yellow palominos may have occurred due to the chemical changes to the pigments during firing, but an accomplished artist learns to control these things; realistic tone of coat color should be rewarded).

• Realistic details like multi-colored eyes, multi-colored hooves, hair texture, pinto mapping, dappling, haloed appaloosa spots, rabicano roaning, etc. require high levels of artistic skill and control; the more details on a piece (shading, pangare, tail frosting, dappling, even the number of different colors on the horse) the more times the horse has been in the kiln. Each turn in the kiln can negatively affect the final outcome; for example. colors can “burn out” or turn weird shades. So the more colors and details, the more difficult the piece was to finish.

• The smaller the horse or the larger the horse, the more difficult it was to make; there is reason why most china horses are “classic” scale!

• With ceramic horses, it is generally much easier to achieve good biomechanics if the piece is on a base; horses with correct motion/gaits that are not anchored to a base are more difficult to engineer and cast. This is even more true if the piece is bone china rather than earthenware.

• As with production run ceramics (OF chinas), crazing and breaks are not in and of themselves flaws; however, breaks should be expertly repaired and minimally visible. Flaws common in OF chinas should never be seen on glazed customs: overspray, hoof color or eye color flowing out of the natural area, flaws in the clear glaze or frosting in a matte glaze, weird greeny or bluey tones, air brush spatters, etc.

• Claybody custom chinas—horses that are resculpted to a new position before the initial, or bisque, firing—require a level of skill and delicacy (and bravery!) that denotes a high level of artistry; these pieces are basically original sculptures as well as one-of-a-kind colors.

• Some colors are hard to predict in fired finishes—realistic nose pinking and blue eyes require skill and planning on the artist’s part, because the more often these colors are fired, the more likely they are to fade.

There are many, many wonderful achievements being made by our top finish artists in glazed custom chinas—perhaps too many to go into here, but a high degree of knowledge and control are needed for the artist to produce realism in this medium; these things should be rewarded in workmanship classes. Things listed below denote excellence in glazed custom workmanship (as with items listed above, sloppiness should be judged as it would in any medium).

• Because ceramic molds are plaster of paris, therefore completely rigid, complex poses are very difficult to achieve; some sculptures are cast in pieces and require extensive assembly by hand after casting, making each piece almost an original sculpture. The more complex the mold, the higher degree of difficulty in making a finished horse.

• Because ceramic materials (earthenware, bone china) require both great delicacy of handling plus a lot of handling to complete, thin legs, tiny ears, body/coat texture, and similar refined details are harder to make in ceramic casting.

• Because ceramic underglazes are not remotely the color when applied that they will be when fired, getting consistent results with color, shading, and coat details such as dappling isn’t easy (in glazed customs, orangey or yellow palominos may have occurred due to the chemical changes to the pigments during firing, but an accomplished artist learns to control these things; realistic tone of coat color should be rewarded).

• Realistic details like multi-colored eyes, multi-colored hooves, hair texture, pinto mapping, dappling, haloed appaloosa spots, rabicano roaning, etc. require high levels of artistic skill and control; the more details on a piece (shading, pangare, tail frosting, dappling, even the number of different colors on the horse) the more times the horse has been in the kiln. Each turn in the kiln can negatively affect the final outcome; for example. colors can “burn out” or turn weird shades. So the more colors and details, the more difficult the piece was to finish.

• The smaller the horse or the larger the horse, the more difficult it was to make; there is reason why most china horses are “classic” scale!

• With ceramic horses, it is generally much easier to achieve good biomechanics if the piece is on a base; horses with correct motion/gaits that are not anchored to a base are more difficult to engineer and cast. This is even more true if the piece is bone china rather than earthenware.

• As with production run ceramics (OF chinas), crazing and breaks are not in and of themselves flaws; however, breaks should be expertly repaired and minimally visible. Flaws common in OF chinas should never be seen on glazed customs: overspray, hoof color or eye color flowing out of the natural area, flaws in the clear glaze or frosting in a matte glaze, weird greeny or bluey tones, air brush spatters, etc.

• Claybody custom chinas—horses that are resculpted to a new position before the initial, or bisque, firing—require a level of skill and delicacy (and bravery!) that denotes a high level of artistry; these pieces are basically original sculptures as well as one-of-a-kind colors.

• Some colors are hard to predict in fired finishes—realistic nose pinking and blue eyes require skill and planning on the artist’s part, because the more often these colors are fired, the more likely they are to fade.

Tuesday, October 6, 2009

Judging Chinas: Breed

I confess, the only thing I know about chinas is that they are fragile. I don't do well with fragile. Things break and then I cry...it's not a pretty picture.

However, guest blogger Melissa Gaulding knows a ton about chinas! The following was written from the judges perspective and should give you insight into what china judges are looking for:

There are a few things restricted by the ceramic medium that should be allowed for in your judging.

• Molding and casting can limit the level of fine detail in hair texture and is to be expected. However, judge lumpish, inexpert manes, tails, or feathering as you would on a resin or customized plastic.

• Glossy glaze can enhance richness of coloring, but reduce visibility of detail, particularly in areas of pure black or pure white.

• Certain colors are difficult to achieve with fired underglazes and overglazes, especially red bays and red chestnuts; truly superior pieces should have similar saturation of color to any cold painted piece. Color shifts are also harder to achieve—where a cold-painted horse might show both golden brown and gray shades within the coat color, this is harder to do in ceramics.

• Hyper-realistic details (individual hairs, striations of color in irises, multi-colored growth rings in hooves, hair-by-hair roaning, etc.) are very difficult to do in ceramic finishes, but oafish application of details should be judged as you would with any other medium.

Labels:

breed class,

china,

custom glazed,

judging standards

Thursday, October 1, 2009

Breed Documentation: The What, When, Why, and How

Today's guest blogger is Amy Widman, owner of this Smarty Jones along with many, many, many National and overall championships:

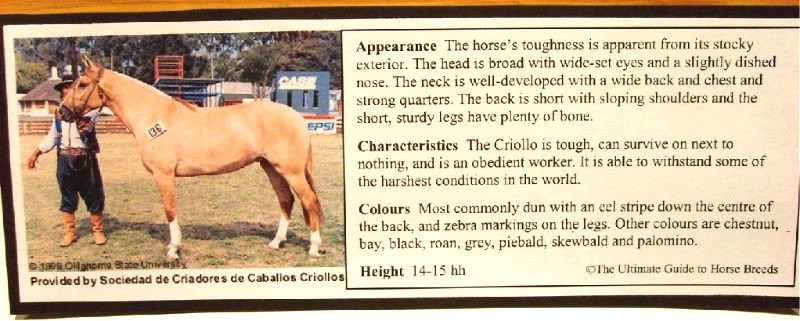

What: For the purposes of Live Showing, “Documentation” generally means reference pictures, breed standards, or other valuable information about the breed you have assigned your model. It is displayed in front of or near your model on the Live Show table to be used as additional information in judging.

When: The most obvious time to use documentation is when your model is representing an obscure or relatively unknown breed. If you’ve been diligent in scouring through breed books and online Google searches to find a really great, new, rare, or odd breed, then it is best to share that new-found information with your judge. Show them that you did your homework and know your breed anatomy and standards. Some judges may have heard of your special breed, but others may not.

Have you heard of the Karabair? (Me neither)

Another good time to supply documentation is if you have a common breed, but with a twist. Maybe you found a unique color that is not well-known within the breed, or an example of a real life horse that shows a different body type than what is automatically thought of in breed standards. Some examples would be Pinto Thoroughbreds or extremely stocky Australian Stock Horses (which are usually thought of as reflecting more sport-type conformation).

Or, maybe you have a pretty common breed or cross in mind for your model, but you’ve found a photo of a real horse that matches your model’s body type and color *perfectly*. This would be a good time to set that picture right in front of your model to show the judge that “yes, my model is a realistic representation of this breed/color/type and here is the proof in the photo of this real horse.” A warning though: do not overuse this form of documentation. Every horse, in every class, doesn’t need a picture matching the model.

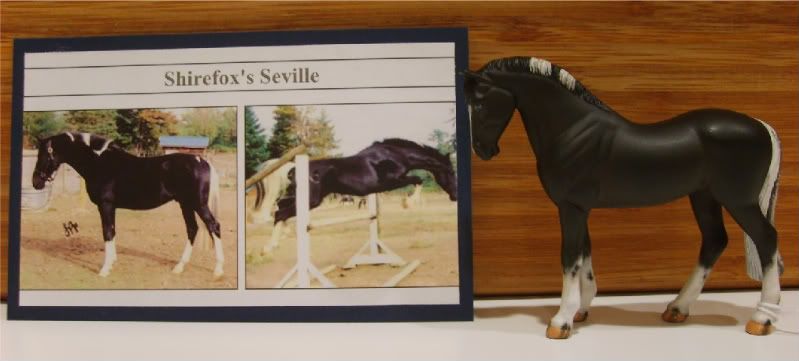

Click for big

Why: No matter how wonderful and knowledgeable a judge is, NO JUDGE KNOWS EVERY COLOR, STANDARD, AND TYPE OF EVERY BREED THROUGHOUT HISTORY. So, help them out and provide documentation. If a judge comes across a breed they’ve never heard of, or are questioning if a certain breed comes in the color your model is representing, they may choose to err on the safe side and not place your horse over a model that they know more about.

In terms of the amount of information to include on your documentation, less is more! The judge does not have time to read through pages of information about a breed. If it’s a little known breed, include some info about basic characteristics, color, and their uses, with one or two pictures. For those more common breeds, stating the breed or cross breeds with some simple pictures will suffice. Using clear pictures and easy-to-read font is always a plus!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)